Editor’s Note: Linn Davis continues our conversation about public participation and the health of our democracy. As an urban planning aficionado, he draws upon the teachings of the incomparable Jane Jacobs to explore the city as a microcosm of democracy.

The most influential book in modern city planning begins: “This book is an attack on current city planning….”

Quite the opening salvo.

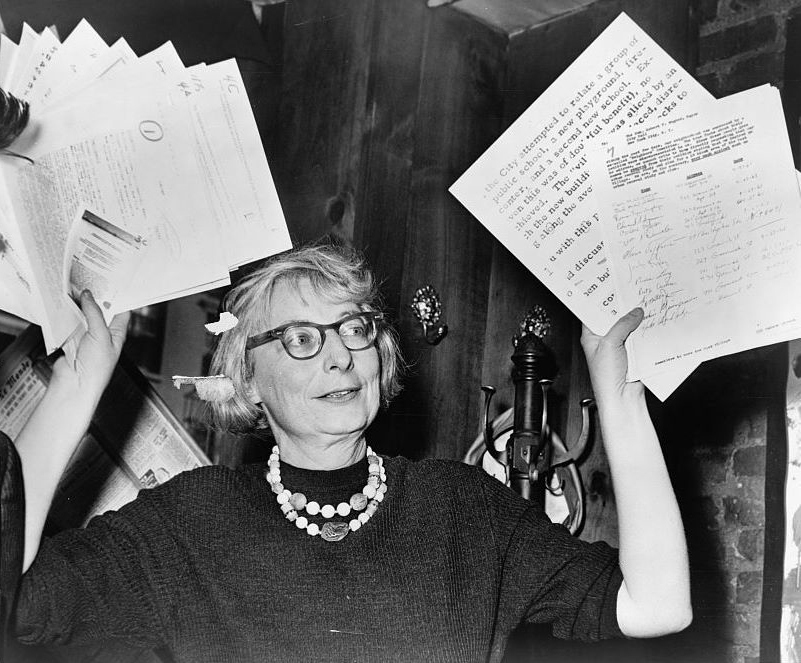

That bold line is the start to The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Jane Jacobs’ 1961 treatise on urban life and space. And though Death and Life has occupied a place on the top shelf of urban planning literature for decades, it’s a book whose sometimes combative, often entertaining statements ought to be equally appreciated in the broader world of public engagement. With a new documentary out this year on Jacobs’ life and work, perhaps it’s time we took a look back at Death and Life and its essential lessons for democracy as a whole.

Jacobs was decidedly not a nonpartisan figure – her opposition to the Vietnam War, for example, prompted her move to Canada in 1968 – but she was hardly an easily pigeon-holed partisan, either. Her contemporary adversaries were elites of all stripes, and many of her ideas have become so decidedly uncontroversial over the years that they verge on a national consensus. And whatever Jacobs’ personal politics, her primary message is plainly universal: believe in people to determine what’s best for themselves.

What’s more, though Death and Life contains plenty of urban wonkery, the book goes far beyond a critique of the built environment; Jacobs’ overarching argument was for democracy. She saw cities as messy, motley, organic bodies whose nervous systems were not arterial streets but people. She found cities to be inherently democratic in their self-organization, and she resented any attempts to force that democracy out of them.

There is probably no profession in the last half-century that has experienced a more comprehensive sea-change in its received wisdom than has urban planning, and this is largely a credit to Jacobs’ wake-up call: that we ought to move from the impersonal and authoritarian to the personal and democratic. The plans for cities, Jacobs believed, must derive from a genuine striving for high-quality public engagement – both on the street and in the planning bureau. Planning, she argued, was more a democratic art than a technical science.

Indeed, whatever one thinks of Jacobs’ particular urban ideas, it’s hard to deny her basic genius: that placing people back in conversations about cities results in better cities. “There is no logic that can be superimposed on the city,” she wrote in a 1958 Fortune magazine article; “people make it, and it is to them, not buildings, that we must fit our plans.”

And so it is with all elements of our public decision-making. We cannot hope to start over and create utopian cities or utopian societies from scratch, and we should not. Human beings don’t suffer utopias gladly. What utopian urban places were built – think housing projects in Chicago or Stuy Town in New York – have rarely aged well. Rather, we must take the organic monster we’ve inherited – born, as it is, of centuries of human ingenuity and trial-and-error – and simply help it become “more perfect.” Not perfect; more perfect. And while technical knowledge is vital to that cause, the improvement of democracy must grow from its users upward. Or in Jacobs’ language: people make it, and it is to them that we must fit our government.